The flute is a very old instrument. According to Wikipedia, a flute discovered recently in Germany may be the oldest musical instrument ever found – perhaps as old as 43,000 years!

The Indian god Krishna is said to be an expert flute player, and is featured

playing one in carvings dating back 4,500 years.

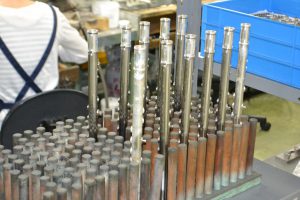

There are a great number of kinds of flutes – Pan flutes, double flutes, flutes with no keys, flutes with lots of weird keys,

flutes made of wood, bone, ivory, bamboo, clay, and iron, flutes lined with paper, flutes made with gold, silver, and platinum.

flutes made of wood, bone, ivory, bamboo, clay, and iron, flutes lined with paper, flutes made with gold, silver, and platinum.

The kind we’ll be discussing on this page is the Western transverse flute – in other words, the kind we’re used to seeing in the Western hemisphere, the kind seen in today’s modern bands and symphony orchestras.

The kind we’ll be discussing on this page is the Western transverse flute – in other words, the kind we’re used to seeing in the Western hemisphere, the kind seen in today’s modern bands and symphony orchestras.

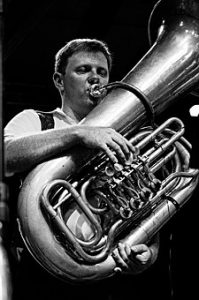

The ‘Score Order’ in the title refers to the musical score, a large document that lists all the instruments required for a piece to be played by a band or orchestra, and it lists them in pitch order, from highest pitch to lowest pitch.

In traditional pieces, the piccolo will be listed as the highest instrument,  at the top of the score, and the tuba, or maybe the string bass, will be listed at the bottom, because it plays the lowest pitches.

at the top of the score, and the tuba, or maybe the string bass, will be listed at the bottom, because it plays the lowest pitches.

The flute, our focus in this post, plays the second highest pitches, so it’s listed second. In the case where a piccolo is not required, the flute will be listed first.

Let’s say you wanted a flute. You have several options to acquire one. You could buy one – new or used. You could rent one, also new or used. You could borrow one.

When you borrow one, it’s likely to be from a friend or relative. Think very carefully about this. When Aunt Edna’s flute comes back from it’s experience at your house, used, somewhat dinged up and needing repairs, how will that affect your relationship with Edna?

Maybe it’s better to buy or rent.

Buying one involves a number of choices. American maker or foreign? Open hole, or plateau system (closed hole)? Low B key, or not? Case cover, backpack style case, hard case?

My 35 years as an instrument repair technician has allowed me a view to information you might find useful.

Let’s look at the maker issue. Clearly, your student needs a reliable instrument that’s also good-enough looking that he or she is not embarrassed to take it out of the case at band or orchestra.

Information about the various makers would be valuable.

In general, the old-line American makers (Armstrong, Gemeinhardt, Emerson, and a few others) have been successfully building and selling flutes in the USA for generations.

Relative newcomers to the American market include Yamaha, Pearl, Altus, Prelude, and Jupiter. All these makers have very good reputations for making well-built and well-warranted instruments.

When buying or renting a new instrument, flutes from these makers are ones that can be counted on for quality and durability.

All acceptable new flutes will come with some kind of case, a tuning/cleaning rod, an perhaps some maintenance items. As with any complicated thing that’s also new to you, be sure to read and follow directions on assembly and maintenance.

Used instruments are a very different story. It is possible to rent used flutes from several reputable online companies, including RentMyInstrument.com

Other companies handling used (they’re often billed as ‘like new’) flutes include NEMC, Inc. nemc.com, and Music and Arts Centers link These last two usually depend on a local affiliate music store to fulfill your contract wishes.

Buying a used flute will involve similar skills to buying a used car – locate a flute, research the brand and model, get an independent technician to look it over for repair and maintenance issues, get an experienced teacher to play test it, negotiate a price based on value and needed repairs, fix it, buy it and take it home.

As of this writing, there are 22,542 flutes listed for sale on Ebay, with prices ranging from $50 to $24,000. How to choose? Here’s a link to a decent beginner flute on Ebay. And, in case you have interest, here’s the link to the one for $24,000!

To begin, check out only those brands listed above. All others are very recent to the Western band instrument manufacturing business, and I guarantee they are not experienced makers, and they’re not using high quality materials.

How could they be, when you can buy a brand new one of their Pacific Rim instruments, shipped from China, for under $50? Their cost of production is down around $10. Even if it plays out of the box, I guarantee it will be a lamp kit in two years.

A very high quality student model flute made in the US, Japan, or Europe will retail at about $500 as of this writing.  Those instruments are built of the best available parts, by craftsmen who have been building flutes for years, and their reputations have been made on quality products.

Those instruments are built of the best available parts, by craftsmen who have been building flutes for years, and their reputations have been made on quality products.

Further, let’s say that you already know something about flutes, and are so thrilled about the flute that you’re looking to start collecting them.

There’s several ways to go here.

One way is to collect the older Western transverse flutes. This would get you into the realm of older European makers, including those who only made wooden flutes.

The truly great names in flutes must include that of Theobald Boehm (1794-1881), and Louis Lot (d. 1890).

Boehm was single-handedly responsible for the widespread use of metal tubes for flute making, a result of his extensive research and experimentation, searching for better tone and intonation than was possible in a wooden flute.

Louis Lot was a world class flutemaker, his company produced around 10,000 instruments before finally being sold to Strasser-Marigaux-LeMaire in about 1960.

The Rudall, Carte companies are also worthy of consideration. There are several variants:

- George Rudall, London

- Rudall and Rose, Covent Garden

- Rudall, Rose and Co., London

- Rudall, Rose, Carte, and Co., The Strand

- Rudall, Carte, and Co., London

There are literally thousands of historical flute makers. A good quality reference for the more notable makers is An Index of Musical Wind- Instrument Makers by Lyndsay G. Langwill, out of print, but still available.

Like all collections, you will need to narrow your interests in order to do a good job of collecting.

As an example, you should check out the Dayton C. Miller flute collection, currently at the Library of Congress in Washington, D.C. There are about 1,600 flutes in that collection, and it is said to be the most comprehensive flute collection in the world.

A further sub-specialty might be to start collecting just head joints. There may have been even more of these than makers of complete flutes.

Collecting flutes can be an exhilarating experience, so focus your desires, and give it a go!

– all images on this page, except those provided by Amazon, were gathered from duckduckgo.

– We welcome your comments!

The reason that this musical word is Italian (and a great many other musical words, like allegro – fast, piano – soft, and col legno – a bowing term for violinists, meaning with the wood of the bow), is that when the Renaissance rolled around in Firenza – Florence, Italy in the 1400’s, music was just one of the arts that was heavily influenced, and the terms just stuck, moving with musicians all over the world.

The reason that this musical word is Italian (and a great many other musical words, like allegro – fast, piano – soft, and col legno – a bowing term for violinists, meaning with the wood of the bow), is that when the Renaissance rolled around in Firenza – Florence, Italy in the 1400’s, music was just one of the arts that was heavily influenced, and the terms just stuck, moving with musicians all over the world. So, back to piccolo, the instrument. It’s a small and very similar version of the flute, which is familiar to most folks. The normal flute is about as long as your arm, the piccolo is about 11″ (66cm) long.

So, back to piccolo, the instrument. It’s a small and very similar version of the flute, which is familiar to most folks. The normal flute is about as long as your arm, the piccolo is about 11″ (66cm) long. While almost all modern flutes are made from metal, the piccolo can be made from metal or wood or plastic. The plastic ones have black color mixed in with the plastic to make them look like wood.

While almost all modern flutes are made from metal, the piccolo can be made from metal or wood or plastic. The plastic ones have black color mixed in with the plastic to make them look like wood. I like to use car analogies, because they’re

I like to use car analogies, because they’re  easy for many people to grasp, so here’s one for piccolos. A Yugo was a car, and the Bentley is a car. They will both get you from A to B (provided the Yugo is running!). They both have 4 tires and a steering wheel. Beyond that, the differences between them are vast. Technology, comfort, convenience, warranty, and safety are nowhere similar between these two cars.

easy for many people to grasp, so here’s one for piccolos. A Yugo was a car, and the Bentley is a car. They will both get you from A to B (provided the Yugo is running!). They both have 4 tires and a steering wheel. Beyond that, the differences between them are vast. Technology, comfort, convenience, warranty, and safety are nowhere similar between these two cars. using industry-standard materials, traceable back to their makers (the plastic, the nickel-silver tubes, the nickel-silver keys, the stainless keywork mounting rods, the stainless – or white gold – springs that operate the keys, the heat-treated pivot screws, and more).

using industry-standard materials, traceable back to their makers (the plastic, the nickel-silver tubes, the nickel-silver keys, the stainless keywork mounting rods, the stainless – or white gold – springs that operate the keys, the heat-treated pivot screws, and more). What sort of quality can you expect for a musical instrument whose cost of production is US$10?

What sort of quality can you expect for a musical instrument whose cost of production is US$10? and head joint tubes, the solder sticking all the parts together will be of a cleaner alloy, the keys and other metal parts will be thick enough to be repairable for generations, the solder joints will all be smooth and strong, the stainless rods and screws that hold the bits together will have been machined correctly and cleanly (no burrs to catch your fingers – or lips!) , and the instrument will play in tune, both with itself, and with the rest of the band/orchestra.

and head joint tubes, the solder sticking all the parts together will be of a cleaner alloy, the keys and other metal parts will be thick enough to be repairable for generations, the solder joints will all be smooth and strong, the stainless rods and screws that hold the bits together will have been machined correctly and cleanly (no burrs to catch your fingers – or lips!) , and the instrument will play in tune, both with itself, and with the rest of the band/orchestra. but be careful about the rental contract. Some are actually rent, where you must give the instrument back to the owner when you’re done with it, and you have never owned the piccolo, others say ‘rent’ when they are actually ‘rent-to-own’ contracts. In the ‘rent-to-own’ scenario, you’re buying the piccolo over time, and will have payed about 1.5 to 2x the retail price over that time.

but be careful about the rental contract. Some are actually rent, where you must give the instrument back to the owner when you’re done with it, and you have never owned the piccolo, others say ‘rent’ when they are actually ‘rent-to-own’ contracts. In the ‘rent-to-own’ scenario, you’re buying the piccolo over time, and will have payed about 1.5 to 2x the retail price over that time. success – choose wisely!

success – choose wisely!

How many French horn players does it take to replace a light bulb? Four, one to screw in the bulb, and the other three to check for valve string adjustments.

How many French horn players does it take to replace a light bulb? Four, one to screw in the bulb, and the other three to check for valve string adjustments.

his character is always introduced by the French horn. The sounds made by expert French horn players are featured in the sound tracks of a great number of movies, such as “Braveheart”, “Wyatt Earp”, “Red Dawn”, “Dances with Wolves”, “Cowboys”, “Mask of Zorro”, “Cocoon”, the “Star Trek” movies, “Field of Dreams”, “Glory”, and a huge number of others.

his character is always introduced by the French horn. The sounds made by expert French horn players are featured in the sound tracks of a great number of movies, such as “Braveheart”, “Wyatt Earp”, “Red Dawn”, “Dances with Wolves”, “Cowboys”, “Mask of Zorro”, “Cocoon”, the “Star Trek” movies, “Field of Dreams”, “Glory”, and a huge number of others.

The haunting, romantic sounds of the French horn have come to be associated with movie scenes involving horseback riding, chases, heroes, the forest, outer space, feelings of love, ships-on-the-water, storms, impending conflict, and moments of longing romance, among many others.

The haunting, romantic sounds of the French horn have come to be associated with movie scenes involving horseback riding, chases, heroes, the forest, outer space, feelings of love, ships-on-the-water, storms, impending conflict, and moments of longing romance, among many others. A full-orchestra score always includes a tuba. The least-known, and likely the most abused instrument of the orchestra is also one of the most important.

A full-orchestra score always includes a tuba. The least-known, and likely the most abused instrument of the orchestra is also one of the most important.

can’t be heard. When the problem is resolved, you go back to hearing the group as a whole, without noticing the bass.

can’t be heard. When the problem is resolved, you go back to hearing the group as a whole, without noticing the bass.

Take a guitar, as an example, in this case we’ll use a classical guitar. And it will make more sense if we start by describing the student, or entry level, instrument. This is a nylon-string instrument, plain nickel-plated tuning peg gear frames, plain tuning peg buttons, 2-piece back with no inlay, plain cedar top with no ornament around the sound hole, entry-level (read cheap) strings, and a very plain bridge. Absolutely a no-frills classical guitar.

Take a guitar, as an example, in this case we’ll use a classical guitar. And it will make more sense if we start by describing the student, or entry level, instrument. This is a nylon-string instrument, plain nickel-plated tuning peg gear frames, plain tuning peg buttons, 2-piece back with no inlay, plain cedar top with no ornament around the sound hole, entry-level (read cheap) strings, and a very plain bridge. Absolutely a no-frills classical guitar. The step-up model from this same manufacturer might look like this: gold-plated tuning peg gear frames, gears, and screw heads, patterned tuning peg buttons, 2-piece back with inlay on the seam, cedar top with wood inlay rosette, silver-plated string windings, and a bridge cut in a slight pattern.

The step-up model from this same manufacturer might look like this: gold-plated tuning peg gear frames, gears, and screw heads, patterned tuning peg buttons, 2-piece back with inlay on the seam, cedar top with wood inlay rosette, silver-plated string windings, and a bridge cut in a slight pattern.

All of the features, with the exception of the strings, do not affect the sound in any way, they are all appearance features. Generally, the features which might improve the sound are found in the pro models. These might include a 1-piece back, specially trimmed interior bracing, improved fitting of the neck to the body block, a bridge made of denser wood, harder nut and saddle material, and very nice strings.

All of the features, with the exception of the strings, do not affect the sound in any way, they are all appearance features. Generally, the features which might improve the sound are found in the pro models. These might include a 1-piece back, specially trimmed interior bracing, improved fitting of the neck to the body block, a bridge made of denser wood, harder nut and saddle material, and very nice strings. It’s the same with the wind instruments, brass and woodwind. As before, we’ll start with the description of the beginner trumpet. A beginner trumpet is made of lacquered brass, has nickel-plated valves, has brass inner and outer tuning slides, has a 2-piece bell, and has stamped waterkeys. The step-up

It’s the same with the wind instruments, brass and woodwind. As before, we’ll start with the description of the beginner trumpet. A beginner trumpet is made of lacquered brass, has nickel-plated valves, has brass inner and outer tuning slides, has a 2-piece bell, and has stamped waterkeys. The step-up  model might be made of silver-plated brass, have Monel valves, have nickel-silver outer tuning slides, a one-piece hand-hammered bell, and Amado waterkeys. With the exception of the hand-hammered bell, none of these features on the step-up affect the sound at all.

model might be made of silver-plated brass, have Monel valves, have nickel-silver outer tuning slides, a one-piece hand-hammered bell, and Amado waterkeys. With the exception of the hand-hammered bell, none of these features on the step-up affect the sound at all.

Back when I had my store, I would often see a comparison shopper, generally a young woman with a young family (we’ll call her Tammi), who came in with a question. “I need a clarinet for Julie, who starts middle school band in a week, what do you have for cheap?”

Back when I had my store, I would often see a comparison shopper, generally a young woman with a young family (we’ll call her Tammi), who came in with a question. “I need a clarinet for Julie, who starts middle school band in a week, what do you have for cheap?” could be purchased for about $700, or rented for $38 per month. $700 was out of her budget, but she was a little bit shy about the ‘rental’ contract, which indicated that she would own the instrument after 36 months, when she will have paid $1,368 for her $700 clarinet. On a month-to-month basis, it might have been manageable, and regular maintenance was included, which made sense, given that Julie is a beginner, and accidents do happen. Tammi has learned to read these contracts.

could be purchased for about $700, or rented for $38 per month. $700 was out of her budget, but she was a little bit shy about the ‘rental’ contract, which indicated that she would own the instrument after 36 months, when she will have paid $1,368 for her $700 clarinet. On a month-to-month basis, it might have been manageable, and regular maintenance was included, which made sense, given that Julie is a beginner, and accidents do happen. Tammi has learned to read these contracts. the ones they have built over the years, but making the parts lighter and thinner, they can do it cheaper, making the sale more profitable for them. Lighter and thinner is not what you want to hear when choosing a clarinet for a beginner. Beginners are going to be a bit rough on the instrument until they learn how to handle it successfully. The older methods of construction are often more robust, and will last longer. Many times, I’ve worked on 50 year old American-made instruments, still in good shape, that are now on their 3rd generation of beginner student!

the ones they have built over the years, but making the parts lighter and thinner, they can do it cheaper, making the sale more profitable for them. Lighter and thinner is not what you want to hear when choosing a clarinet for a beginner. Beginners are going to be a bit rough on the instrument until they learn how to handle it successfully. The older methods of construction are often more robust, and will last longer. Many times, I’ve worked on 50 year old American-made instruments, still in good shape, that are now on their 3rd generation of beginner student! A well-made, refurbished instrument is often a much better buy than a new one. I always kept a good stock of Vito clarinets on hand. Vito, an American-made student clarinet, is thought by me and many other technicians to be the best student model clarinet ever made. These are well-engineered, stoutly-made clarinets that will stand up to several generations of beginners. Because of several American makers consolidating, Vito is no longer made, but there are plenty of them around. I would buy or trade for these clarinets, them refurbish them to play and look like new, and sell them for about $400.

A well-made, refurbished instrument is often a much better buy than a new one. I always kept a good stock of Vito clarinets on hand. Vito, an American-made student clarinet, is thought by me and many other technicians to be the best student model clarinet ever made. These are well-engineered, stoutly-made clarinets that will stand up to several generations of beginners. Because of several American makers consolidating, Vito is no longer made, but there are plenty of them around. I would buy or trade for these clarinets, them refurbish them to play and look like new, and sell them for about $400. Tammi could arrange for this to happen herself, and save even more money. She could buy a good Vito on Ebay for $25+shipping, locate a shop to refurbish it, spend about $300, and have a shiny, well-made clarinet, in perfect shape, and be out of pocket about $350.

Tammi could arrange for this to happen herself, and save even more money. She could buy a good Vito on Ebay for $25+shipping, locate a shop to refurbish it, spend about $300, and have a shiny, well-made clarinet, in perfect shape, and be out of pocket about $350. There are similar deals available on all the common beginner instruments – flute, clarinet, saxophone, trumpet, trombone, baritone horn. One good way to start is to locate an instrument repair shop that will work with you on this type of project. Recommendations from private teachers is one way to go, another is to visit

There are similar deals available on all the common beginner instruments – flute, clarinet, saxophone, trumpet, trombone, baritone horn. One good way to start is to locate an instrument repair shop that will work with you on this type of project. Recommendations from private teachers is one way to go, another is to visit